It’s an old post from Tumblr, but it just keeps turning back up in my social media feeds. Kind of like cultural appropriation.

Yes, I’m going to talk about cultural appropriation here but let me actually start at the bottom of this post. We’ll work our way up from there. There’s one aspect of this whole situation that I am surprised that no one mentioned: the fact that the final respondent states that they are Japanese and *in Japan.*

This is important because the participation of white foreigners in Japanese culture in Japan happens within very different cultural and historical contexts than it does in America. For the most part, white foreigners in Japanese media (movies, anime) and at festivals, religious shrines, or participating in cultural events is viewed as sometimes meaningfully diverse in an otherwise homogeneous State culture, sometimes exploitative (directed at the white person) for marketing, or as a reflexive commentary on Japanese culture for the purposes of art or critique. In short, a Japanese person in Japan is going to view an American in the trappings of Japanese culture differently than a Japanese or Asian person in America would.

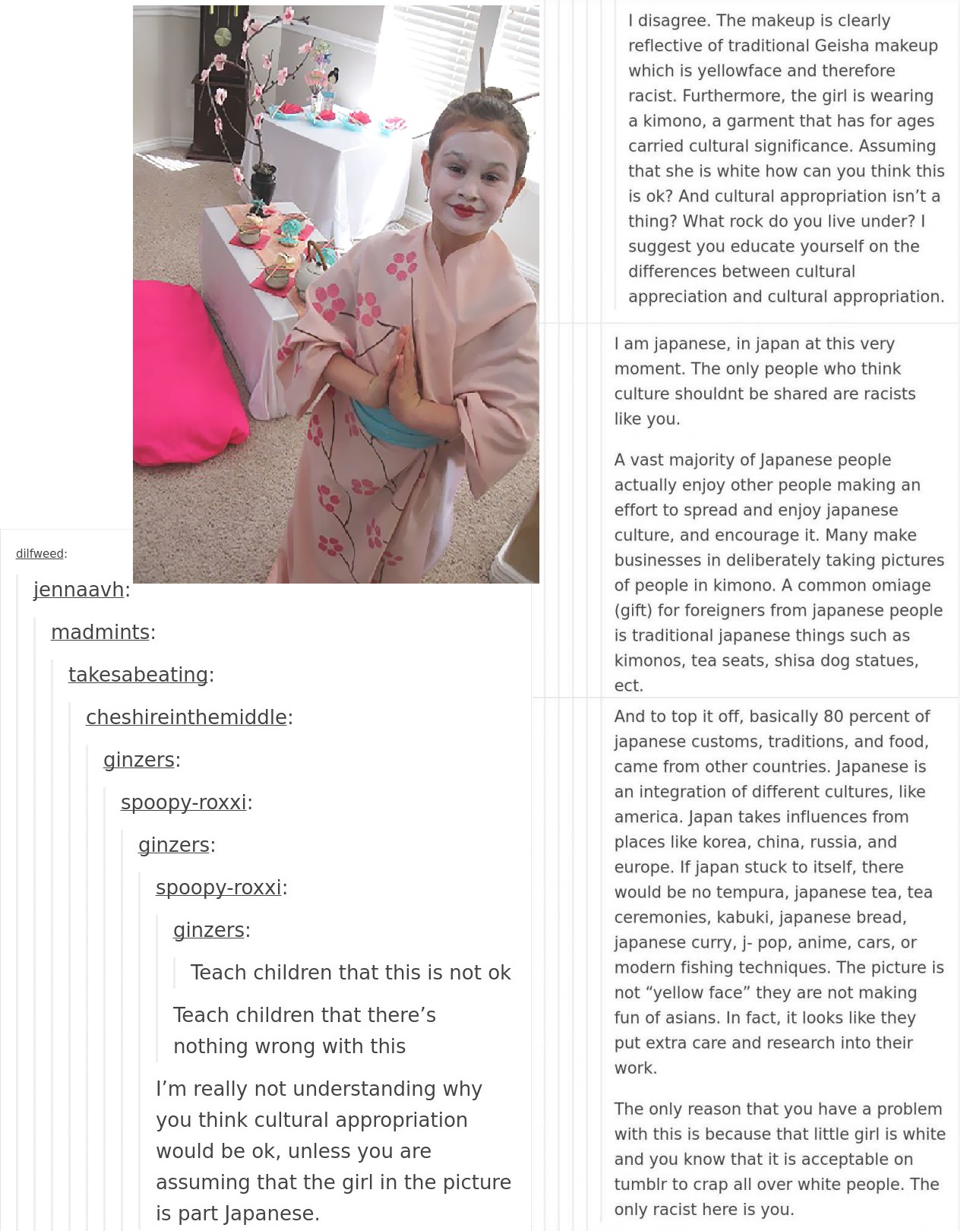

It is likely that if this young Caucasian girl had had a Geisha birthday party in Japan, very few, if anyone, would have found that offensive. But this tea party birthday probably didn’t happen in Japan, it happened in America; where whitewashing and appropriation are situated in different contexts. That’s why I find this meme’s implied “down with those PC SJWs!” message irritating. Cultural appropriation is a real thing but it is also a complex issue and not easily reduced to an internet message board. But my post here isn’t actually so much about whether or not this particular little girl’s birthday party is appropriation–it’s about how we, on the ostensibly progressive left, are using (and misusing) this term.

Let’s think back to Starbucks for a moment. Remember when there was that big blow up about Starbucks “using Italian”?

From a popular culture standpoint, the concept of “cultural appropriation” has often been used by liberals and progressives in such a way that unfortunately validates whiteness and pushes white supremacist narratives about what culture is and how it should be preserved. What this means, in other words, is that it is not uncommon for white people to scream “cultural appropriation” as a way to set other cultures aside, put them up on a pedestal, and claim that no one be allowed to engage with them on any level. This is because cultural appropriation has been used to label just about any instance where two or more cultures (broadly defined) come into contact with one another and begin to blend, borrow, or exchange (something cultures do and have done all the time). Starbucks using Italian was never really an example of appropriation because in current American structures of white supremacy, Italian culture has already been subsumed into whiteness, not set aside from it.

Where Cultural Appropriation as a concept is useful is when we are describing the process of sublimation into whiteness as dominant culture. For the non-academic, that means where something generally marked as being from a specific (non-white, non-European) culture is “whitened” all the while preserving the concept of the original culture as lesser (i.e., white people in corn rows rapping is awesome and edgy; black people in corn rows rapping is “ghetto”). Or, that parts of the culture in question have become worthy of our attention or consumption because they have encountered whiteness or been made white (i.e, a white “powwow” or in the ever growing issue of “culture as costume” during Halloween). For the Japanese Geisha birthday party, the question at hand really then would have been about whether or not the costumes, make-up, and trappings were being “taken away” from Japan and made better, more palatable, or more acceptable because the children were white. Or whether or not the Geisha or tea ceremonies were being mocked or disrespected outside of their typical contexts. And those are much harder questions to consider and which require more complex critical thinking and nuance about time, place, and history. This is because cultural appropriation is an aspect of systemic inequalities of power.

In short, cultural appropriation is all about context. Is the cultural element in question “out of place” in some way or not? How so? Is it being used in such a way that comes at the expense of the people it indicates? Is it being misused or caricatured? Who benefits from the use and depiction and who doesn’t?

Furthermore, while “misappropriation” would potentially be more accurate semantically, the history of cultural appropriation as a term most often refers to a white person making money off of something taken from another non-white, usually marginalized, culture. But part of the problem of using the term is that “cultures” in the West are typically viewed as static, unchanging, and existing within specific boundaries of place or person (short heads-up, that’s not how culture actually works). Such static cultures can then easily be commodified and turned into objects for sale (the proceeds of which do not generally go to the people whose culture it is). Aside from money though, the problem with the view of “Culture as Static” is that it is also implicitly informed by white supremacy in the way that whiteness is changing and advancing while other cultures simply exist as they always have.

The thing is, there are plenty of issues around Starbucks and their use of an Italian vocabulary in order to make money (which is more a question of what kind of signifiers we use to denote refinement in America). And there are plenty of issues one might have with a white American family throwing their little girl a “Japanese” birthday party. But a discussion about coffee which is labeled as “French” and “Italian” to disguise its mass-market origin, or a discussion about what exactly it is you think “Japanese” culture really means and how you choose to perform it, is a discussion which is different from cultural appropriation. That discussion is about what “authenticity” means and who “owns” culture, who doesn’t, and in what ways.

In the end, the best shorthand one can use to determine if an instance of cultural borrowing or blending is trending into the realm of appropriation is to, once again, ask questions: 1) who benefits from this exchange and who is potentially harmed? and 2) why are you choosing this particular cultural object or idea as opposed to anything else? And as always, context matters.

I’m sad to say, though, that the answers may not be easy. But they’ll get you further than Tumblr.